Alex Colville’s career spanned over seventy years and comprised hundreds of works. His working life was very much in the public eye, from his first exhibitions in the 1950s until the touring retrospectives that capped his exhibition career in the 1990s and 2000s. He never retired, but worked on new paintings well into his eighties. At his death he was the best-known artist in Canada, and his body of work includes some of the most iconic images ever created in this country.

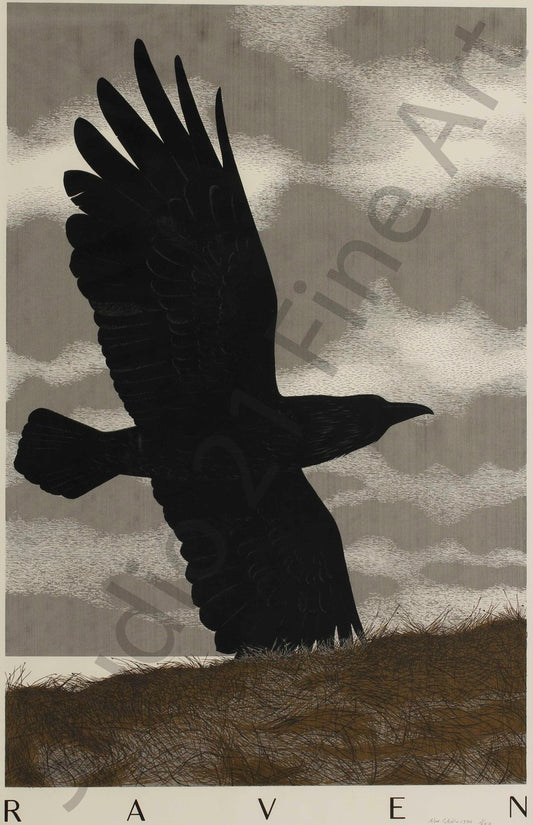

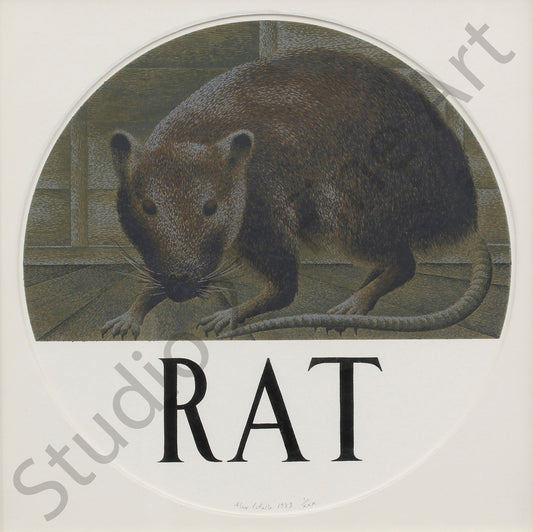

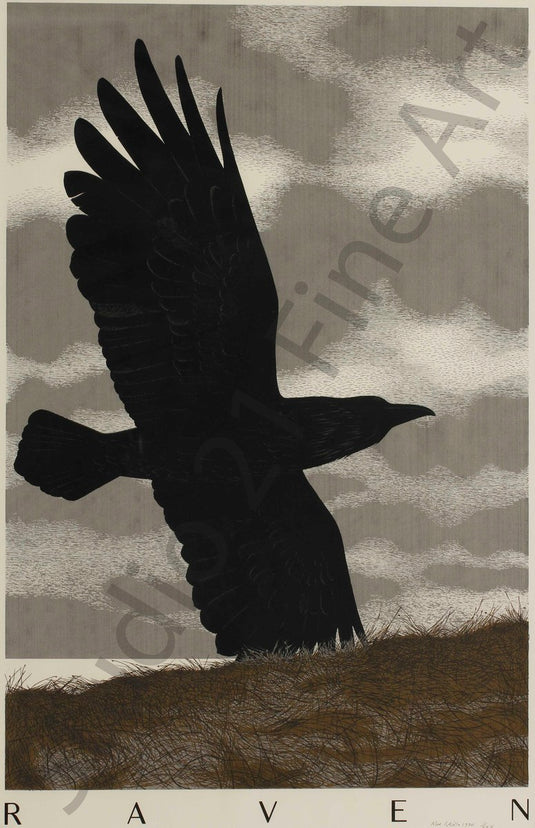

Consistent in his dedication to figuration and allegorical compositions, Colville kept returning to the same major themes: family life, desire, individual will, and relationships between men and women, humans and animals, nature and the machine, and, above all, order and chaos. His paintings are distinctive and easily recognizable, marked by his careful, unified brushwork and meticulously arranged compositional structures. Another key process for the artist was printmaking, which appealed to Colville in its inherent limits and capacity to create multiples.

From 1955, in addition to his paintings, Colville worked with serigraphy. Usually in print runs of between twenty and seventy, Colville’s serigraphs, or silkscreen prints, should be considered of equal weight to his paintings, and they show little difference from his panels in subject matter and composition. Colville made thirty-five screen prints between 1955 and 2002, and in 2013 he donated an entire set to Mount Allison University, where he first studied and later taught. The donation comprises the only complete set of his screen prints in any public or private collection.

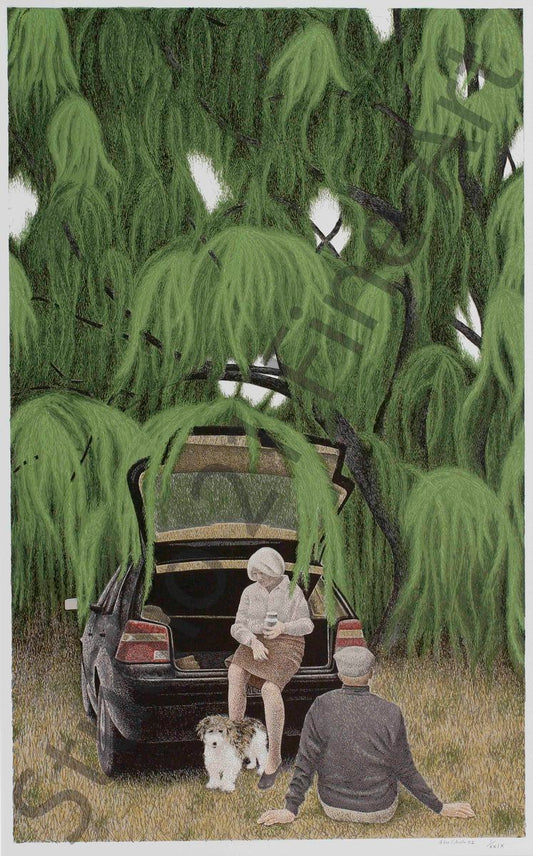

Serigraphs are made by pushing ink through a fine mesh onto a substrate, with the areas that are not to be that particular colour blocked by a stencil or other medium. A different screen is used for each colour. Colville made all his prints himself and never reproduced his paintings in this medium. Rather, each print is a unique composition. After Swimming, 1955, was Colville’s first published serigraph. This image reflects a theme that Colville returned to often throughout his career—the relationship between a man and a woman, specifically between husband and wife, as evidenced by the use of himself and his wife, Rhoda, as the models. His last serigraph was Willow (2003) which again depicts Colville and his wife Rhoda.

Though a complicated and demanding process, serigraphy took much less time than his paintings and allowed Colville to work in multiples. The relative immediacy of the technique (colours are applied over the whole surface and images appear at once rather than being gradually built up with thousands of brush strokes), the unforgiving nature of making images with colour applied through screens, and the inherent limits of the process, drew Colville’s interest: “One of the appeals of print-making is the discipline of the printing technique; in painting almost anything is possible—in print-making there are limitations of means; the concept must be adapted to a more economical mode of expression.”21 Interestingly, he didn’t branch out into other kinds of printmaking, nor did he, after the 1940s, create watercolours or drawings as finished artworks. He focused unswervingly on paintings and screen prints.

Excerpts from: ALEX COLVILLE, LIFE & WORK By Ray Cronin original source

Consistent in his dedication to figuration and allegorical compositions, Colville kept returning to the same major themes: family life, desire, individual will, and relationships between men and women, humans and animals, nature and the machine, and, above all, order and chaos. His paintings are distinctive and easily recognizable, marked by his careful, unified brushwork and meticulously arranged compositional structures. Another key process for the artist was printmaking, which appealed to Colville in its inherent limits and capacity to create multiples.

From 1955, in addition to his paintings, Colville worked with serigraphy. Usually in print runs of between twenty and seventy, Colville’s serigraphs, or silkscreen prints, should be considered of equal weight to his paintings, and they show little difference from his panels in subject matter and composition. Colville made thirty-five screen prints between 1955 and 2002, and in 2013 he donated an entire set to Mount Allison University, where he first studied and later taught. The donation comprises the only complete set of his screen prints in any public or private collection.

Serigraphs are made by pushing ink through a fine mesh onto a substrate, with the areas that are not to be that particular colour blocked by a stencil or other medium. A different screen is used for each colour. Colville made all his prints himself and never reproduced his paintings in this medium. Rather, each print is a unique composition. After Swimming, 1955, was Colville’s first published serigraph. This image reflects a theme that Colville returned to often throughout his career—the relationship between a man and a woman, specifically between husband and wife, as evidenced by the use of himself and his wife, Rhoda, as the models. His last serigraph was Willow (2003) which again depicts Colville and his wife Rhoda.

Though a complicated and demanding process, serigraphy took much less time than his paintings and allowed Colville to work in multiples. The relative immediacy of the technique (colours are applied over the whole surface and images appear at once rather than being gradually built up with thousands of brush strokes), the unforgiving nature of making images with colour applied through screens, and the inherent limits of the process, drew Colville’s interest: “One of the appeals of print-making is the discipline of the printing technique; in painting almost anything is possible—in print-making there are limitations of means; the concept must be adapted to a more economical mode of expression.”21 Interestingly, he didn’t branch out into other kinds of printmaking, nor did he, after the 1940s, create watercolours or drawings as finished artworks. He focused unswervingly on paintings and screen prints.

Excerpts from: ALEX COLVILLE, LIFE & WORK By Ray Cronin original source

Alex Colville

Alex Colville